Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin

Paper presented at the 29th Annual Symposium of the European Association for Aquatic Mammals (EAAM), Genoa, 9-12 March 2001

The Zanzibar Cetacean Conservation Project

Marco Tocchetti *^, Alessandro Bortolotto ^, Narriman Jiddawi °

^ Zoönomia, via Don Carlo Gnocchi, 5 - 40128 Bologna (BO), Italy

* Università degli Studi di Cagliari, Dipartimento di Biologia Sperimentale, Sezione di Fisiologia Generale - Cittadella Universitaria di Monferrato, Strada Statale 554 - 09100 Cagliari (CA), Italy

° Institute of Marine Sciences, P.O. Box 668, Stone Town, Zanzibar, Tanzania

Abstract

The island of Unguja (Zanzibar) along with the island of Pemba forms the Archipelago of Zanzibar that is separated from the mainland of East Africa (Tanzania) by a 36 km (22.5 miles) channel.

Several cetacean species have been reported in these waters; nevertheless very little information is presently available regarding occurence, distribution and abundance. For this reason in October 1999 we started the Zanzibar Cetacean Conservation Project (ZCCP) for the study and protection of cetacean species ranging in the Archipelago waters, with particular reference to the indo-pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) in the area off Stone Town (the main town of Unguja).

Animals were detected during visual surveys at sea, aboard a 10 m local wooden boat powered by a 25 HP engine, both using pre-defined single line transects as well as "ecological" routes, and occasionally from selected points along the coasts (Stone Town, Mtoni, Bububu) and a few small islands (Chapwani, Bawe) of the channel.

During the cruises we collected data on environmental parameters as well as data regarding the animals encountered (all photographed for further analyses). Behavioural data collection was also performed but limited to three classes only: travel (T), activity (A) and inactivity (I).

During this research we observed bottlenose (both T. truncatus and T. ?aduncus) and indo-pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa plumbea "form" according to what has been previously described) as well as humpback whales.

We strongly feel that this area is of critical importance considering the lack of general reliable information on East African cetacea, the reduced effort of presently ongoing cetacean research in the area, and eventually the presence of a poorly known species such as Sousa plumbea whose status is unknown and whose preference for coastal habitats makes it a potentially vulnerable species.

The Archipelago of Zanzibar (Indian Ocean) is situated off the coast of Tanzania from which is separated by a relatively shallow channel (36 km at its nearest point with a maximum depth of 70 m and around 45 as an average)(Fig.1). It consists of two main islands, Pemba and Unguja (Zanzibar) as well as a number of smaller islands (Chumbe, Bawe, Changuu, Kibandiko and Chapwani in our study area). Unguja is a big island (85 x 39 km) and the seat of the main town of the Archipelago (Stone Town). The western part of the island is characterised by the presence of mangroves sometimes interrupted by sandy or rocky beaches. The small islands facing this coastline share its features; additionally there are a few sandbanks (such as Pange), emerging only during the low tide in areas slightly southward and westward of Stone Town. The tide range varies from about 1,5 to 3 m; in a few areas there are coral reef formations, but generally speaking it is very limited in this part of the island. On the contrary, on the southern, northern and especially eastern part of Unguja, the depth increases markedly and coral reefs are more consistent, therefore showing slightly different coastal features, with only a single big mangrove area in the middle of the eastern coast (Chwaka Bay).

Several cetacean species are potentially ranging in the Archipelago waters even though very little information is presently available. Species known to occur are bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus and T. aduncus), Indian humpback (Sousa plumbea), spinner (Stenella longirostris) and Risso's dolphin (Grampus griseus) as well as humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) and sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus). Furthermore, as gathered through the analysis of historical data found at the Zanzibar Archives, the false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) is also reported with a mass stranding of 44 individuals including a newborn on the 2nd of december 1933 at Mtoni. For more details on historical data see Tab. I.

On February 1999, the Italian association Fondo per la Terra/ Earth Fund told us about the potentially critical situation in Zanzibar mainly due to the increased tourism-related activities. We then decided to have a general overlook of the area (February 1999) and start a research project (October 1999) aimed at studying the occurrence of cetaceans in these waters as well as the influence of human activities on their presence. After several considerations, we decided to focus our efforts on the area around Stone Town, from Kama promontory (to the north) to Chukwani (to the south)(Fig. 2). Occasionally we also monitored the area around Kizimkazi, to the southwest of the island (Fig. 2), where bottlenose dolphins are exposed to a massive uncontrolled "whale-watching" activity, as well as the area around Matemwe, to the northeast, where several cetacean sightings are reported (mainly spinner dolphin and humpback whales). All of our surveys where made on 10 m wooden boats powered by a 15HP engine, with an average speed of 10 km/h (Fig.3). Occasionally we carried out also shore-based observations, mainly to the north of Stone Town (Fig. 2). In the period between October and November 1999 a total of 13 surveys were made; a total of 43 on summer 2000. During the surveys we used two different methods: 'single line transects' (SLT) and 'ecological survey' (ES).

(SLT) To estimate the occurrence of cetaceans we outlined five different regularly covered linear routes. A speed of 10 km/h was maintained while looking forward and on both sides in a stretch of approximately 200 m (on each side); each transect was 12 km long (weather permitting) (Fig.2). In case of a positive sighting we also noted down the estimated distance from the boat and the angle formed with the boat direction.

(ES) we followed pre-planned routes (Fig. 2) in areas where the environmental conditions best suited the humpback dolphin's habitat (i.e. within the depth of 25 m according to the literature); for this reason we tried to maintain a distance of about 250 m from the shore whenever possible.

All of above mentioned surveys (both types) have been carried out in three different time periods: morning, zenith and afternoon. During these surveys several data were constantly monitored: water temperature, cloudiness and type of clouds, sea conditions (Beaufort scale), wind direction, visibility, boat speed and GPS position as well as the presence of other species and human activities. In case of positive contact with cetaceans we also noted down group size, behavioural budget (travelling, activity and inactivity), breathing rate. Whenever possible, pictures were also taken for our Photo-ID program. We used Nikon F60 cameras equipped with Tamron 80-300 Zoom with 400 ISO films for both colour slides and B/W prints.

According to our data, the most common species occurring in this area is definitely the Indian humpback dolphin, Sousa plumbea (G. Cuvier, 1829) sensu Ross et al. (1994) and Rice (1998). All of our sightings in this area belong to this species with the exception of two unknown delphinids (but definitely not Sousa sp.) spotted in 1999 (October, 25th 1999), a bottlenose dolphin entangled in the nets (August, 4th 2000) off Changuu and a non humpback delphinid (probably a bottlenose) close to Bawe (August, 12th, 2000). Furthermore, we highlight a few sightings of humpback whales in the channel between Unguja and Tanzania: at Chumbe in 1999 (Omar Ali Amir, pers. commn.), in several occasions in our study area in late August - early September 2000 and at Kizimakzi (September 5th, 2000) ( (Fig. y).

Starting from September 2000 onward, this project is run by Zoönomia, with the support of the Institute of Marine Sciences, Zanzibar. Genetic analyses are being carried out to deepen the systematic on the species occurring in the area. Furthermore, research agreements are currently being made in order to activate a cooperation between the Beit el-Amani (the Zanzibar Museum) and the Natural History Museum in Milan and to start bioacoustic analyses on humpback dolphins ranging in the area, in cooperation with the CIBRA, Pavia University.

Acknowledgments

We kindly acknowledge Mario Mariani, vice-consul of Italy in Tanzania, for his support and friendship, Omar Ali Amir, Claudia Fachinetti, Roberto Induni, Cristina Pilenga for their help, and eventually Silvia Ceppi and Fondo per la Terra / Earth Fund for partially supporting this project at its beginning.

REFERENCES

Rice, D.W., 1998

Marine Mammals of the world - Systematics and distribution.

Special publication number 4 - The Society for Marine Mammalogy

Ross, G.J.B., Heinsohn, G.E., Cockroft, V.G., (1994)

Humpbacks dolphins Sousa chinensis (Osbeck, 1765), Sousa plumbea (G. Cuvier, 1829) and Sousa teuszii (Kukenthal, 1892). Pages 23-42 In: (S.H.Ridgway and R. Harrison, eds.) Handbook of Marine Mammals. Volume 5. The first book of dolphins. Academic Press, San Diego, CA

Paper presented at the 15th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society (ECS), Rome, 6-10 May 2001

On the presence of the humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) in Zanzibar

Alessandro Bortolotto1,4 , Marco Tocchetti1,2 and Narriman Jiddawi3

- 1 Zoönomia, via Don Carlo Gnocchi, 5, 40128 Bologna (BO), Italy (E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. )

- 2 Università degli Studi di Cagliari, Dipartimento di Biologia Sperimentale, Sezione di Fisiologia Generale - Cittadella Universitaria di Monserrato, Strada Statale 554, 09100 Cagliari (CA), Italy (E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. )

- 3 Institute of Marine Sciences, P.O. Box 668, Stone Town, Zanzibar, Tanzania (E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. )

- 4 Università degli Studi di Padova, Dipartimento di Scienze Animali, Strada Romea 16, 35020 Agripolis - Legnaro (PD), Italy

Introduction

Several cetacean species have been reported in the waters surrounding Zanzibar (Stensland et al., 1998; Tocchetti et al., 2001), nevertheless very little information is presently available regarding occurence, distribution and abundance. On February 1999, one of the authors (Bortolotto) went to Zanzibar for a general overlook of the area; then, in cooperation with the Institute of Marine Sciences in Zanzibar, it was decided to start a research project (October 1999) aimed at studying the occurrence of cetaceans in these waters as well as the influence of human activities on their presence (Tocchetti et al., 2001), with particular reference to the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea).

The Archipelago of Zanzibar (Indian Ocean) is situated off the coast of Tanzania from which is separated by a relatively shallow channel (36 km at its nearest point with a maximum depth of 70 m and around 45 as an average). It consists of two main islands, Pemba and Unguja (Zanzibar) as well as a number of smaller islands (Chumbe, Bawe, Changuu, Kibandiko and Chapwani, in our study area)(Fig. 1). Unguja is the biggest island of the Archipelago (85 x 39 km) and the seat of its main town (Stone Town). The western part of the island is characterised by the presence of mangroves sometimes interrupted by sandy or rocky beaches. The small islands facing this coastline share its features; additionally there are a few sandbanks (such as Pange), emerging only during the low tide in areas slightly southward and westward of Stone Town. The tide range varies from about 1,5 to 3 m; in a few areas there are coral reef formations, but generally speaking it is very limited in this part of the island. On the contrary, on the southern, northern and especially eastern part of Unguja, the depth increases markedly and coral reefs are more consistent, therefore showing slightly different coastal features, with only a single big mangrove area in the middle of the eastern coast (Chwaka Bay). After several considerations, we decided to focus our efforts on the area around Stone Town, from Kama promontory (to the north) to Chukwani (to the south). Occasionally we also monitored the area around Kizimkazi, to the southwest of the island, where bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops spp.) are exposed to a massive uncontrolled "dolphin-tours" activity, as well as the area around Matemwe, to the northeast, where several cetacean sightings are reported, mainly spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris) and humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae).

Materials and methods

All of our surveys were made on 10 m wooden boats powered by a 15HP engine. Occasionally we carried out also shore-based observations, mainly to the north of Stone Town. In the period between October and November 1999 a total of 13 explorative surveys were made; 43 pre-defined ones on summer 2000. During the 2000 surveys we used two different methods: 'single line transects' (SLT) and 'ecological survey' (ES), while in 1999 we made random surveys.

(SLT) to estimate the occurrence of cetaceans we outlined five different regularly covered linear routes. A speed of 10 km/h was maintained while looking forward and on both sides in a stretch of approximately 200 m (on each side); each transect was 12 km long (weather permitting) (Fig.1). In case of a positive sighting we also noted down the estimated distance from the boat and the angle formed with the boat direction.

(ES) we followed pre-planned routes (Fig. 1) in areas where the environmental conditions best suited the humpback dolphin's habitat (i.e. within the depth of 25 m according to the literature); during each ES we tried to maintain a distance of about 250 m from the shore whenever possible.

All of above mentioned surveys (both types) have been carried out in three different time periods: morning, noon and afternoon. During these surveys several data were constantly monitored: water temperature, cloudiness and type of clouds, sea conditions (Beaufort scale: 3 as upper limit), wind direction, visibility, boat speed and GPS position as well as the presence of other species and human activities. In case of positive contact with cetaceans we also noted down group size, behavioural budget (travelling, activity and inactivity), breathing rate. Whenever possible, pictures were also taken for our Photo-ID program. We used Nikon F60 cameras equipped with Tamron 80-300 Zoom with 400 ISO films for both colour slides and B/W prints; furthermore we also used a video camera in order to record complex behavioural sequences.

Results

All cetacea sighted during the coastal ES were humpback dolphins. No other species has been sighted during these coastal surveys. The only exceptions are the bottlenose dolphin in Fig 2, presumably of the ?aduncus type (genetic analyses are presently being done), found dead entangled in the nets near Changuu Island, as well as the sighting of two delphinids (presumably Tursiops sp.) on Sep 14th, 2001 near Pange (in the only ES relatively offshore, the one we called ‘islands’). On the other hand, only one humpback, a big sized adult heading offshore, has been sighted during the SLT routes (on Aug 23rd, 2000), 2.4 km from the island of Bawe - c.a. 6 km from Stone Town. This case is similar to the one described by Corkeron (1990) and cited in Karczmarski et al. (2000). Therefore this is one of the few reports of humpback dolphins occurring several kilometers from the shore. As in the case previously cited our sighting occurred in a relatively shallow area (<30 m). Nevertheless, most of our sightings took place predominantly inshore as expected.

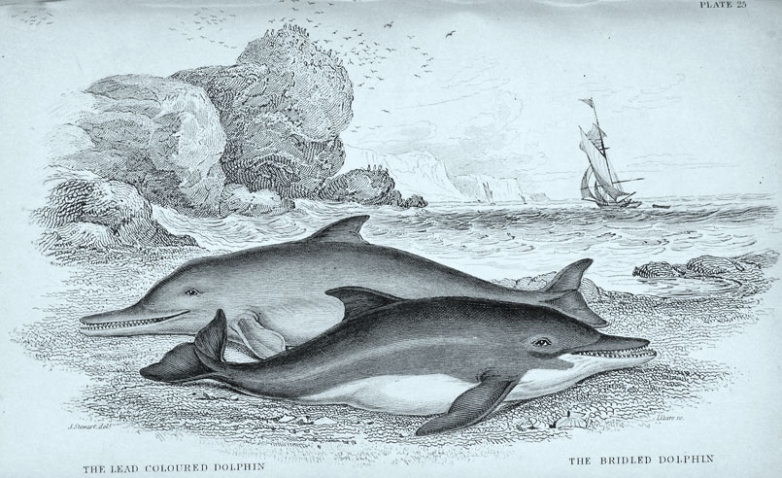

The humpback dolphins observed during this survey clearly belong to the "Indian Ocean form" Sousa plumbea based on dorsal fin structure according to what has been previously described (Ross et al., 1994), being the dorsal fin of the animals that we observed quite elongated and thickened basally, as shown below and according to Rice (1998)(Fig. 3).

The schools that have been sighted during our 1999 surveys ranged from 3 to about 8 dolphins (n= 6). In all the occasions we noticed the presence of one or two calves. This was always in association with groups containing more than one adult, as previously described (Saayman and Tayler, 1979).

During the season 2000, the groups ranged from 1 to 8 (n= 19); only one calf has been sighted (Aug 5th) in association with 4 other individuals less than 100 m from the shore to the south of Stone Town. As previously described (Saayman and Tayler, 1979) the humpback dolphins that we observed usually swam quite slowly even though in a particular occasion (october 1999) we noticed a general increase of the overall school's activity, possibly due to what appeared to be a socio-sexual interaction between two individuals (apparently adults) involved in courting-like behaviour. The animals were isolated from other members of their group and showed a vigorous activity with 'helical interchanging of their relative position' as previously described in a long-term study in Algoa Bay, South Africa (Karczmarski et al., 1997).

During this preliminary study several pictures have been taken in order to document the species' presence as well as to start a catalogue for future photo-identification studies. Previous researchers have pointed out the difficulty in identifying humpback dolphin given the features of this species' dorsal fin and suggesting the use of alternative techniques such as the matrix photo-identification (Karczmarski and Cockcroft, 1998) versus a more traditional approach (Defran et al., 1990). All the pictures are presently being examined by different researchers. So far we managed to successfully identify only one individual while many others showed distinct markings, the main problems being the difficulty in obtaining good quality pictures, mainly due to the attitude of the animals, and the extreme light conditions. Nevertheless, given the importance of photo-identification to shed some light on the ecology of this poorly known species we will keep on focusing our attention to this method with dedicated surveys on summer 2001.

Several authors have described a characteristic avoidance reaction to boats, rarely permitting close approaches. Nevertheless, during both our 3 weeks period (1999) and the three months spent in season 2000, we never experienced such a tendency. On the contrary, the animals appeared to be quite interested into our boat, often approaching it directly and following our path, indipendently of the calves' presence (1999). A few times they came really close to the research boat (only a few meters away from our cameras) and spent a considerable amount of time with us. As a matter of fact, in several occasions it has been our choice to interrupt the contact because of poor visibility due to the late hour. In our case study, humpback dolphins were often seen in areas heavily used by inshore traffic (i.e.: around the Port of Stone Town) both in February 1999, October 1999 and the season 2000; this is in contrast with what has been observed by Karczmarski (1996) in the area around Port Elizabeth, South Africa, and more in general in Algoa Bay, South Africa, where animals seemed to be particularly disturbed by powerboats (Karczmarski et al., 1997).

By the way, if harassed by a boat, also humpback dolphins in our study area tended to perform avoidance behaviours, normally making longer dives, changing their direction and swimming underwater for a long distance before surfacing. An interesting fact that we noticed during the season 2000, is the tendency of humpback dolphins to be attracted by jet skis. This tendency was clearly seen on several occasions both from the shore and from our research boat.

On one particular occasion we were observing the animals from our boat floating adrift while a jet sky passed by causing all the animals to change their behaviour and actively approach it at a close distance. Humpback dolphins' surfacing-breathing pattern has been described as fairly stereotyped (Karczmarski et al., 1997); as a general tendency, also in our study area they expose their beaks on surfacing, arching the back strongly (Fig. 4) and sometimes raising the flukes on diving (Fig. 5). During our surveys aerial behaviour was relatively infrequent in according to the literature (Karczmarski et al., 1997); nevertheless in a few occasions full vertical leaps, porpoising and breaching were noticed on both seasons 1999 and 2000. During the october 1999 survey, aerial behaviours were performed only by calves while in 2000 we noticed a big adult performing a full vertical leap.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the typically restricted inshore occurence facilitates the implementation of sea and land-based observation. During both seasons we noticed the tendency of the animals to follow a definite pattern southward and northward at different times of the day. This tendency is still under evalutation and will be extensively studied in the future. Furthermore, as pointed out in previous works there is the need to study also their nocturnal behaviour as well as the response to boat traffic. For these reasons, for summer 2001 we are planning to start observations from the land as well as acoustic surveys of the study area, along with the italian CIBRA, University of Pavia. Furthermore an official cooperation with the Milano Museum of Natural History is being established in order to support the activities of the Beit-el-Ameni, the Natural History Museum in Zanzibar.

Acknowledgments

We kindly acknowledge Mario Mariani, vice-consul of Italy in Tanzania, for his support and friendship, Omar Ali Amir for his support and help, Claudia Fachinetti, Roberto Induni, Cristina Pilenga from the University of Pavia for their help, Laura Bonomi for reviewing this presentation and for photo-ID analysis and eventually Fondo per la Terra / Earth Fund for partially supporting this project at its beginning.

REFERENCES

Corkeron, P. J. 1990

Aspects of the behavioural ecology of inshore dolphins Tursiops truncatus and Sousa chinensis in Moreton Bay, Australia. Pp. 285-293. In The Bottlenose dolphin. (Eds. S. Leatherwood, R. R. Reeves). Academic Press Inc.

Defran, R. H., Schultz, G. M. and Weller, D.W. 1990

A technique for the photographic identification and cataloging of dorsal fins of the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus).

Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. (Special Issue 12): 53-55

Karczmarski, L. and Cockcroft, V. G. 1998

Matrix photo-identification technique applied in studies of free-ranging bottlenose and humpback dolphins.

Aquatic Mammals, 20: 143-147

Karczmarski, L., Thornton, M. and Cockcroft, V. G. 1997

Description of selected behaviours of humpback dolphins Sousa chinensis.

Aquatic Mammals, 19: 127-133

Karczmarski, L., Cockroft, V. G. and McLachlan, A. 2000

Habitat use and preferences of indo-pacific humpback dolphins Sousa chinensis in Algoa Bay, South Africa.

Marine Mammal Science, 16 (1): 65-79

Rice, D. W. 1998

Marine Mammals of the world - Systematics and distribution.

Special publication number 4 - The Society for Marine Mammalogy

Ross, G. J. B., Heinsohn, G. E. and Cockroft, V. G. 1994

Humpbacks dolphins Sousa chinensis (Osbeck, 1765), Sousa plumbea (G. Cuvier, 1829) and Sousa teuszii (Kukenthal, 1892). Pp. 23-42. In: Handbook of Marine Mammals. Volume 5. The first book of dolphins. (Eds. S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison). Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Saayman, G. S. and Tayler, C. K. 1979

The socioecology of humpback dolphins (Sousa sp.). Pp. 165-226. In: Behaviour of marine animals. Volume 3. Cetaceans. (Eds. H. E. Winn and B. L. Olla). Plenum Press, New York and London.

Stensland, E., Berggren, P., Johnstone, R. and Jiddawi, N. 1998

Marine mammals in Tanzanian waters: Urgent need for status assessment.

Ambio, 27 (8): 771-774

Tocchetti, M., Bortolotto, A. and Jiddawi, N. 2001

The Zanzibar Cetacean Conservation Project.

Poster presentation at the 29th EAAM Annual Symposium, Genoa, Italy